Hunter’s Field Playground sits beneath the Claiborne Expressway in New Orleans on July 18, 2023. Opened nine years ago, the playground is one of the monitoring sites of a new EPA study on the health impacts of the expressway.

Drew Hawkins/Gulf States Newsroom

hide caption

toggle caption

Drew Hawkins/Gulf States Newsroom

Hunter’s Field Playground sits beneath the Claiborne Expressway in New Orleans on July 18, 2023. Opened nine years ago, the playground is one of the monitoring sites of a new EPA study on the health impacts of the expressway.

Drew Hawkins/Gulf States Newsroom

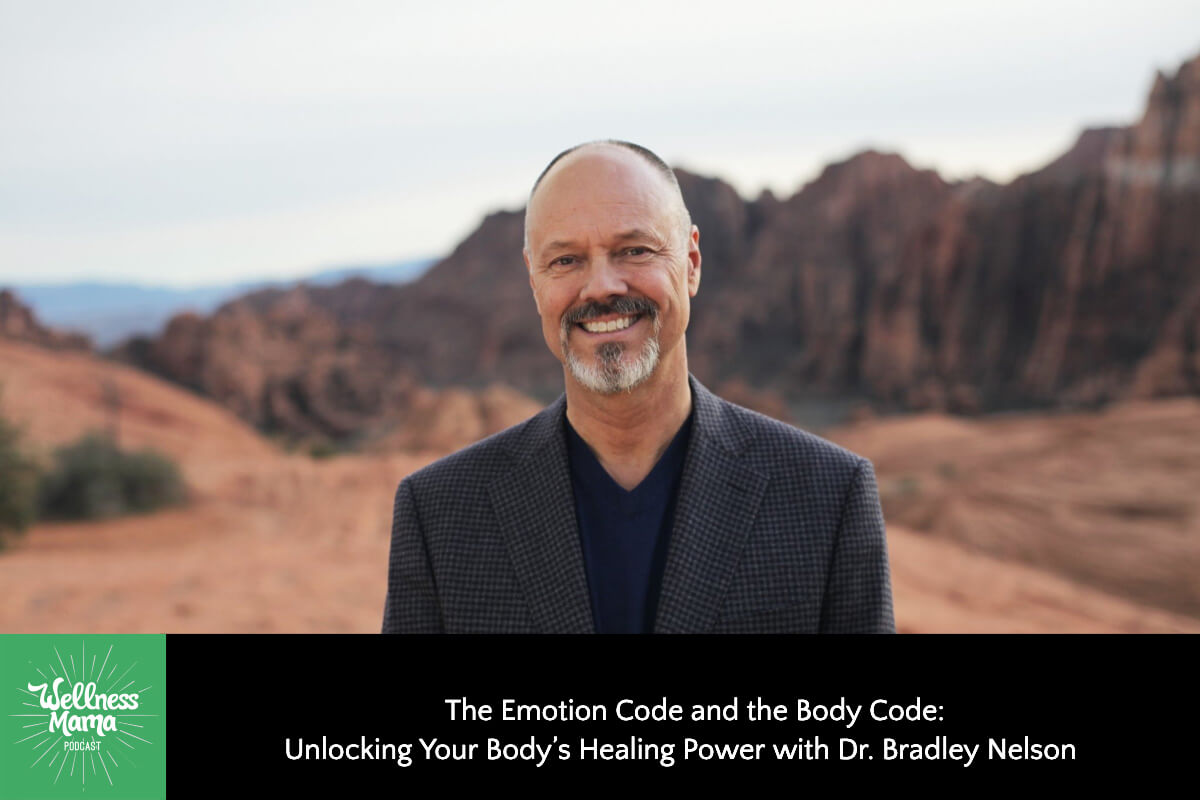

Aside from a few discarded hypodermic needles on the ground, the Hunter’s Field Playground in New Orleans looks almost untouched. It’s been open more than nine years, but the brightly-painted red and yellow slides and monkey bars are still sleek and shiny, and the padded rubber ground tiles still feel springy underfoot.

For people who live nearby, it’s not a mystery why the equipment is still relatively pristine: Children don’t come here to play.

“Because kids are smart,” explains Amy Stelly, an artist and urban designer who lives just over a block away on Dumaine Street. “It’s the adults who aren’t. It’s the adults who built the playground under the interstate.”

Hunter’s Field is wedged directly beneath the elevated roadbeds of the I-10 Claiborne Expressway in the city’s 7th Ward.

There are no sounds of laughter or children playing. The constant cuh-clunk, cuh-clunk of the traffic passing overhead makes it difficult to hold a conversation with someone standing next to you.

“I have never seen a child play here,” Stelly says.

Stelly keeps a sharp eye on this area as part of her advocacy work with the Claiborne Avenue Alliance, a group of residents and business owners dedicated to revitalizing the predominantly African-American community on either side of the looming expressway.

For as long as she can remember, Stelly has been fighting to dismantle the Claiborne Expressway. She’s lived in the neighborhood her entire life and says the noise is oftentimes unbearable.

“You can sustain hearing damage,” she says. “If we were out here all day and it was this loud all day — which it is for the most part — then at some point in time, it would affect our hearing negatively.”

Graduate student researcher Jacquelynn Mornay, with the LSU School of Public Health, shows a noise reading taken beneath the Claiborne Expressway on July 18, 2023, in New Orleans. The decibel levels are similar to that of a motorcycle engine and could cause permanent hearing damage after prolonged exposure.

Drew Hawkins/Gulf States Newsroom

hide caption

toggle caption

Drew Hawkins/Gulf States Newsroom

Graduate student researcher Jacquelynn Mornay, with the LSU School of Public Health, shows a noise reading taken beneath the Claiborne Expressway on July 18, 2023, in New Orleans. The decibel levels are similar to that of a motorcycle engine and could cause permanent hearing damage after prolonged exposure.

Drew Hawkins/Gulf States Newsroom

The Claiborne Expressway was built in the 1960s at a time when the construction of new interstates and highways were a symbol of progress and economic development in the U.S., and urban planning and transportation development were at the forefront of city agendas.

But that supposed progress often came at a great cost for marginalized communities — especially Black neighborhoods.

When it was built, the “Claiborne Corridor” as it’s still sometimes known, tore right through the heart of Treme, one of the oldest Black neighborhoods in the country.

For more than a century before the construction of the expressway, bustling Claiborne Avenue constituted the backbone of economic and cultural life for Black New Orleans.

Then, the oak-lined avenue was home to more than 120 businesses. Today, there are only a few dozen left.

What happened to Claiborne Avenue isn’t unique. Many of the highways that get us from point A to B have an unfortunate racist legacy.

Federal planners often routed highways directly through low income, Black and Brown neighborhoods, dividing communities and polluting the air.

This racist legacy extends all across the country. In Montgomery, Alabama, I-85 cut through the city’s only middle-class Black neighborhood and was “designed to displace and punish the organizers of the civil rights movement,” according to Rebecca Retzlaff, an associate community planning professor at Auburn University.

In Nashville, planners intentionally looped I-40 intentionally swerved around a white community, and sent it plowing through a prominent Black neighborhood, knocking down hundreds of homes and businesses. The list goes on and on.

Recently, the federal government has stated it wants to try to address the problem. An initiative established in the Biden Administration’s Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act called Reconnecting Communities seeks to do just that — reconnect neighborhoods and communities that were divided by infrastructure.

The problem is not everyone agrees on the best way to do that.

Competing visions for the Claiborne expressway

Communities, city and state agencies and organizations across the country submitted proposals seeking federal funding — including one from Stelly’s group, the Claiborne Avenue Alliance. In many ways, their proposal seemed poised to succeed. It’s a textbook example of the racist planning history — even the White House says so in a published statement on the program. But the Alliance’s grant proposal was denied.

Instead, the city of New Orleans and the state of Louisiana jointly submitted a separate proposal, requesting that the federal program cover half the cost of a $95 million plan.

That plan wouldn’t move the freeway out of the neighborhood, but would pay for repairs and maintenance work on the existing stretch of highway, and to try to spruce up the desolate area underneath the highway by building a public market and performance space.

Unlike the Claiborne Alliance’s plan, that proposal was officially approved, but so far, the Louisiana Department of Transportation and Development has only received $500,000.

The city-state proposal does include some improvements that Stelly approves of, such as removing some of the dangerous on- and off-ramps that make it difficult for pedestrians to safely walk through the neighborhoods beneath the expressway. There are also proposed projects aimed at public safety, like better lighting and pedestrian and bicycle lanes.

Stelly calls the idea of creating an entertainment space and market beneath the highway — dubbed the “Claiborne Innovation District” — misguided and ridiculous.

“It’s a foolish idea because you’re going to be exposed to the same thing” as the neglected playground, Stelly says. “You’re going to be exposed to the same levels of noise. It’s not a wise decision to build anything under here.”

Using science to inform policy

Although her group’s proposal was denied, Stelly isn’t giving up. She and her organization are turning to a new strategy: cooperating with a study on the health impacts caused by the expressway. They hope the data will support them in their efforts to remove the highway from their neighborhood.

In addition to noise impacts, the EPA-funded study is also looking at the health impacts of pollution under the Claiborne Expressway — especially harmful pollutants like particulate matter 2.5, or PM 2.5.

Amy Stelly, an artist, urban designer and community activist, stands beneath the Claiborne Expressway on July 18, 2023. Stelly, who lives nearby, is working with the LSU School of Public Health on an EPA study of the noise and air pollution from the highway, and still supports moving this stretch of I-10 away from the historically black community.

Drew Hawkins/Gulf States Newsroom

hide caption

toggle caption

Drew Hawkins/Gulf States Newsroom

Amy Stelly, an artist, urban designer and community activist, stands beneath the Claiborne Expressway on July 18, 2023. Stelly, who lives nearby, is working with the LSU School of Public Health on an EPA study of the noise and air pollution from the highway, and still supports moving this stretch of I-10 away from the historically black community.

Drew Hawkins/Gulf States Newsroom

These microscopic particles, measuring 2.5 microns or less in diameter, are released from the tailpipes of passing vehicles, according to Dr. Adrienne Katner, a professor at the LSU School of Public Health,who is managing the EPA study. They’re so small that when you inhale them they lodge deeply in the lungs. From there, they can migrate to the circulatory system, and then spread and potentially affect every system in your body.

“So the heart, the brain,” says Katner. “If a woman is pregnant, it can cross the placental barrier. So it has a lot of impacts.”

The study is just getting started: Katner and her researchers are now taking preliminary readings with monitors at different points along the expressway. It will likely take two to three years to complete the study and publish the data.

One of the monitoring sites is Hunter’s Field Playground. Graduate researcher Jacquelynn Mornay said the noise levels were as loud as a motorcycle engine up close and could cause permanent hearing damage after an hour or so of exposure. The pollution levels recorded hover around 18 micrograms per cubic meter.

“It should be at most, at most, 12,” said Beatrice Duah, another graduate student researcher. “So it is way over the limits.”

In addition to the playground, there are also homes and businesses lining the area beneath the expressway. The residents and employees are exposed daily to these levels of noise and pollution. While this EPA study is just getting started, it will join a decades-long body of research about how traffic pollution affects the human body. Katner doesn’t expect any surprises from this particular stretch of I-10.

“We’re not inventing the science here,” Katner said. “All I’m doing is showing them what we already know and then documenting it, giving them the data to then inform and influence policy. That’s all I can do.”

‘Removal is the only cure’

Eventually, these findings could help other communities divided by infrastructure across the country, Katner says.

“A lot of cities are going through this right now and they’re looking back at their highway systems,” she says. “They’re looking back at the impacts that it’s had on a community and they’re trying to figure out what to do next. I’m hoping that this project will inform them.”

Stelly isn’t expecting any surprising findings either. She’s always known the air she and her neighbors breathe isn’t safe, she says, but she’s hopeful that having concrete data to support her efforts will do more convince policy makers to address the problem. That could mean taking down the dangerous on-and-off ramps — or scrapping what she considers to be the wasteful idea of putting a market and event space under the highway overpass.

Still, there’s only one true solution here for Stelly, only one way to really right the wrong done to her community.

“Removal is the only cure,” Stelly says. “I’m insisting on it because I’m a resident of the neighborhood and I live with this every day. But the science tells us there’s no other way.”